What is a Quantum Ledger Database?

Update 2024: QLDB will be discontinued in mid 2025, don’t use it for new projects.

This blog introduces you to a database that solves an interesting niche problem: Amazon Quantum Ledger Database (QLDB). We’ll get to the service later, but first, I’m going to set the stage by describing a problem that the service can solve. I’m going to tell you a story - not my own story but one that happened to a colleague. That story made me understand where QLDB-like systems could be beneficial.

A colleague of mine bought a used car some time ago with his partner and thought they had gotten a good deal. Upon researching, they discovered that odometer manipulations (the thing that measures how many kilometers you’ve driven your car) were a common issue with that car model. They got worried and decided to take that car to a licensed dealer and have them look at it. The dealer consulted the records, and sure enough, things looked sketchy. The last time the car had been serviced was around the 300k kilometer mark on the odometer. Now, the odometer showed a little over 100k kilometers. Fortunately, it was possible to undo the purchase, and no money was lost.

That story made me think. Wouldn’t it be great if cars periodically send their odometer data to a central system that securely stores it, detects manipulations, and allows potential buyers to check the odometer history? We’d want this system to ensure the odometer value can only increase, and that data can’t be tampered with - it should be verifiable. Fortunately, an AWS service has these properties: the Quantum Ledger Database (QLDB).

QLDB has a fancy name for an interesting use case. In a nutshell, it allows you to write data to a table and keeps track of all changes to it. You can go back in time and view all changes to a specific record or get a view of the table at a past point in time. On top of that, it allows you to cryptographically verify that the data hasn’t been tampered with.

Let’s talk about some concepts first. A Ledger is an accounting term you may not be familiar with if English is not your first language. It is a way of recording (financial) transactions that makes it possible to view the transactions’ history and the accounts’ current state. It allows you to audit that the accounts match the transaction history and is an important - and often legally mandated - way of keeping records. Transactions here are immutable, meaning they can’t be changed once they happen. If you want to undo a transaction, you can’t remove it from the history. You add a new transaction that undoes the effects.

If this sounds familiar, you might have heard it from one of the most hyped technologies of the past years: the Blockchain. It’s a way of keeping records like this without a central authority to hold the records. It’s complex, compute-intensive, and many claim it’s a solution that’s looking for a problem. While the decentralized nature is fascinating from a tech perspective, it’s overengineered for most real-world use cases. If you’re able to trust a central authority to keep the ledger and can verify transactions, you can omit the decentralized complexity of the Blockchain. This is where the Quantum Ledger Database comes in.

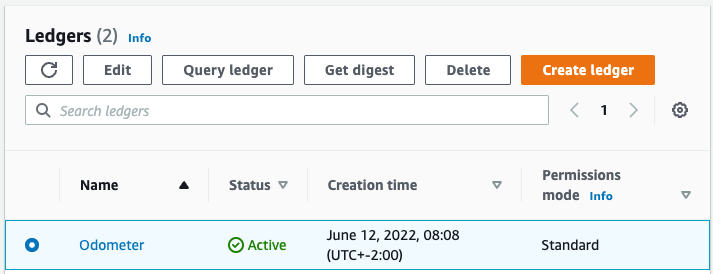

QLDB allows you to create a ledger that acts similar to a schema or table space in a traditional database. Once you’ve created this ledger, you create a table through the SQL-like query language PartiQL that also enables you to interact with the data.

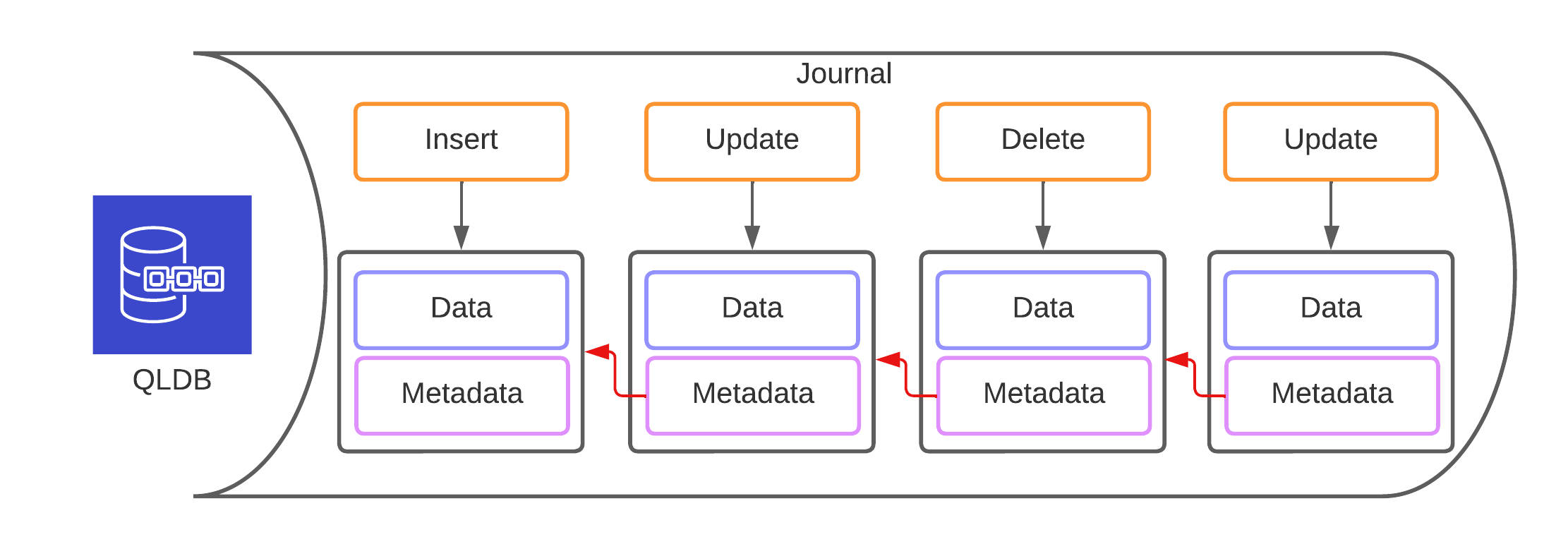

You can insert, update and delete records in the table, and under the hood, QLDB will record all your changes in a journal. This journal is an ordered sequence of data changes. Each change in this journal is linked with the previous chain through cryptographic means. It attaches a so-called digest to each change, which is iteratively computed over all changes until this point.

This allows you to verify the journal’s integrity (chain of changes) by going through each transaction and computing the digest again. If your result matches the recorded digest, data integrity is preserved, and something has been messed with if it doesn’t. Under the hood, QLDB uses Ion to store the data and makes it possible to export it together with the cryptographic information to S3.

If the system only consisted of the journal, it would be of limited usefulness. Another feature is views. By default, all queries you make operate on the User View. The User view contains the most recent version of your data. Another very similar view is the committed view, which has all the data from the user view and additional metadata such as a version counter of each record. You can also dive into the history of changes using the history function - more on that later.

Let’s get back to our problem at hand. We want to track odometer values for cars, so the first thing we have to do is create a table. The PartiQL syntax for this is very close to SQL:

CREATE TABLE odometer_values

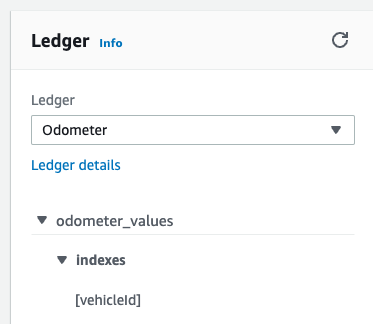

Note that we don’t specify any columns or datatypes here. QLDB doesn’t have a fixed schema. Each document in our table could have a different structure. An id identifies documents that the system generates for them. The id is part of the metadata. It’s not something we can control. In most use cases, we have an additional identifier that our application will use. To allow for efficient queries, we’ll now index this identifier, which I’ve chosen to call vehicleId.

CREATE INDEX ON odometer_values (vehicleId)

This is what our table should look like in the query editor now:

Next, we can add some data using insert statements. The syntax is somewhat similar to SQL, but there is a caveat here. Indexes don’t impose a unique constraint, so I could run this query twice and get two documents with the vehicle id “car-27”. As far as I know, a conditional insert isn’t possible at this point, so you’d have to check if the id already exists beforehand.

INSERT INTO odometer_values

VALUE {'vehicleId': 'car-27', 'odometerValue': 50}

The insert statement returns the document ID of the document that has been created. Now we can update the odometer value under the condition that it doesn’t decrease the value.

UPDATE odometer_values

SET vehicleId = 'car-27',

odometerValue = 200

WHERE vehicleId = 'car-27' AND odometerValue <= 200

If this returns 0 rows, the vehicle id either doesn’t exist, or the odometer value is already higher than the new value. You must check that and create the vehicle id in the former case. In the latter case, that indicates potentially fraudulent activity.

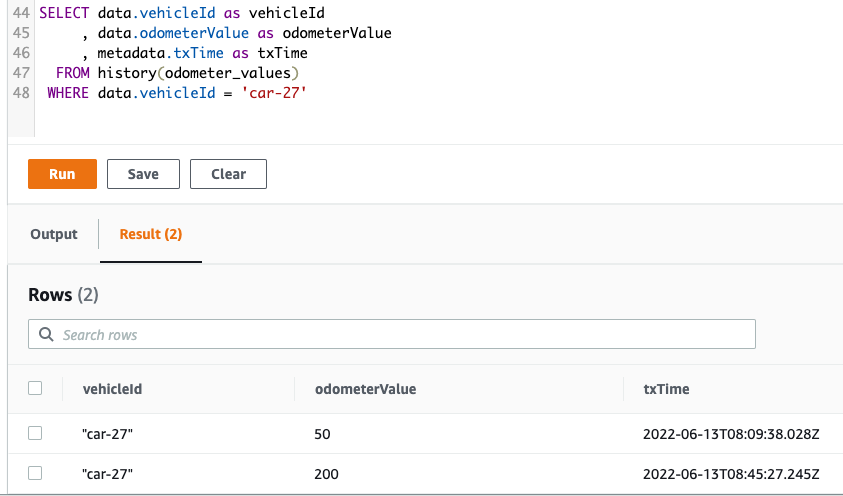

Now that we’ve updated our odometer values, we can check out the history for our record by using the history function. Here, we query the history of the table and filter on the vehicle id we care about. We also only extract some of the values.

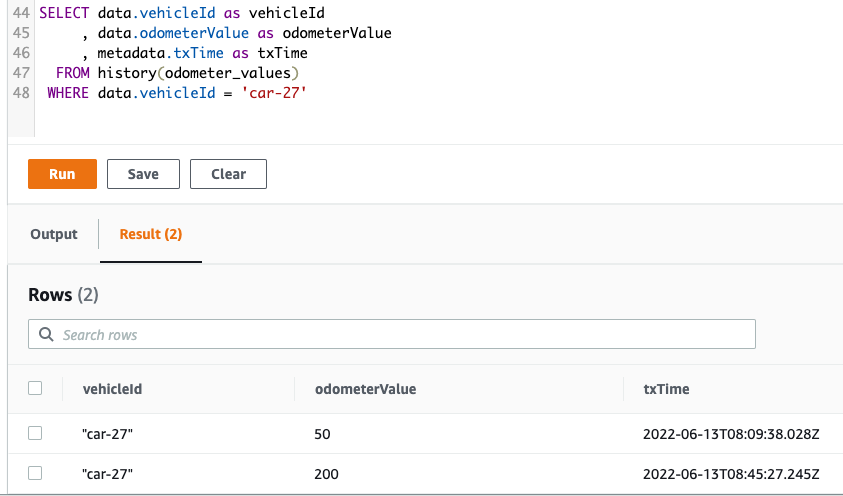

SELECT data.vehicleId as vehicleId

, data.odometerValue as odometerValue

, metadata.txTime as txTime

FROM history(odometer_values)

WHERE data.vehicleId = 'car-27'

The result should look something like this. We can see that the odometer values have increased over time.

Next, we’ll delete the car from the table because it has crashed and is broken beyond repair (kind of a shame after only 200km).

DELETE FROM odometer_values

WHERE vehicleId = 'car-27'

If we rerun our earlier query, we can see that nothing has changed because the history is preserved. We can’t permanently delete data from the table because our journal is immutable - it will always stick around in the history of transactions. This may have implications for legal compliance (think GDPR), so you may need to consider that when working with personally identifiable information (PII). A common approach would be to encrypt the PII before storing it and deleting the key once the data is no longer needed. This means your transaction history would be preserved, but you could no longer decrypt some records.

Another feature I want to highlight is QLDB streams, which allow you to perform change-data-capture and send data to a Kinesis Data Stream, where you can consume it with other services such as Lambda. This can enable compelling use cases. That’s it for now.

Hopefully, you’ve learned something new from this article. If there are any questions, feedback, or concerns, feel free to reach out to me via the social media channels in my bio.

— Maurice

Update 2024: QLDB will be discontinued in mid 2025, don’t use it for new projects.

The cover image is based on a Photo by Fractal Hassan on Unsplash