Deep Dive into DynamoDB streams and the Lambda integration

You have probably seen this architecture before. A DynamoDB table holds data and a Lambda function that gets triggered whenever data changes in the table. It’s almost ubiquitous in Serverless architectures, and one of the everyday use cases is to maintain aggregation items in a table. Today we’ll dive deeper into this superficially trivial architecture and explore how DynamoDB streams works, what the Lambda service does in the integration, and which knobs you have available to tweak the setup.

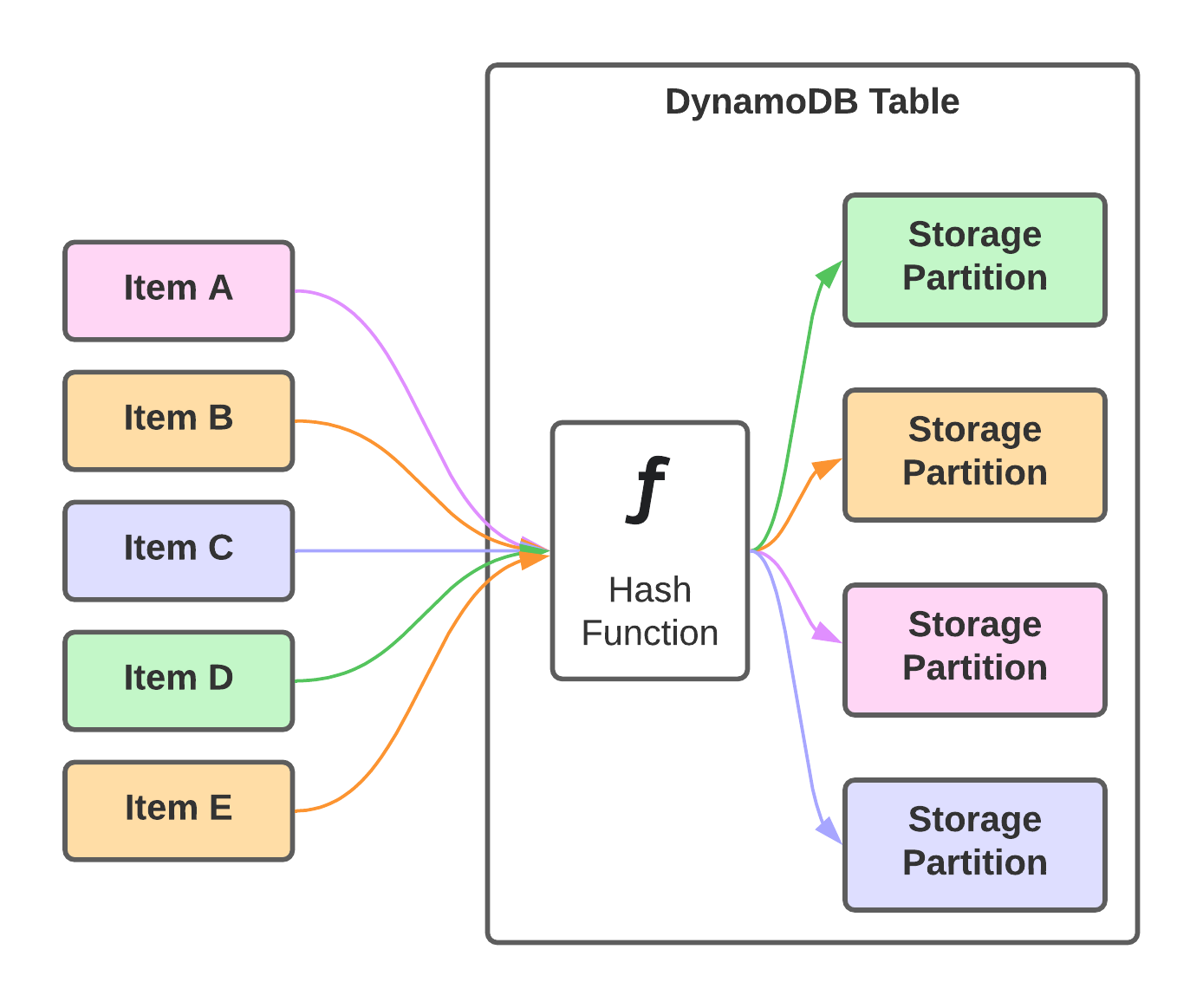

Storage partitions make up DynamoDB tables, and each of them can hold up to 10GB of data and delivers a certain amount of read-write throughput. Each item in the table has at least a partition key, which determines through a hash function on which storage partition the item resides. The primary key identifies each item comes in two varieties depending on the setup of the table. It can either be a simple primary key equivalent to the partition key or a composite primary key consisting of a partition and sort key. The latter is used to sort items that share the same partition key.

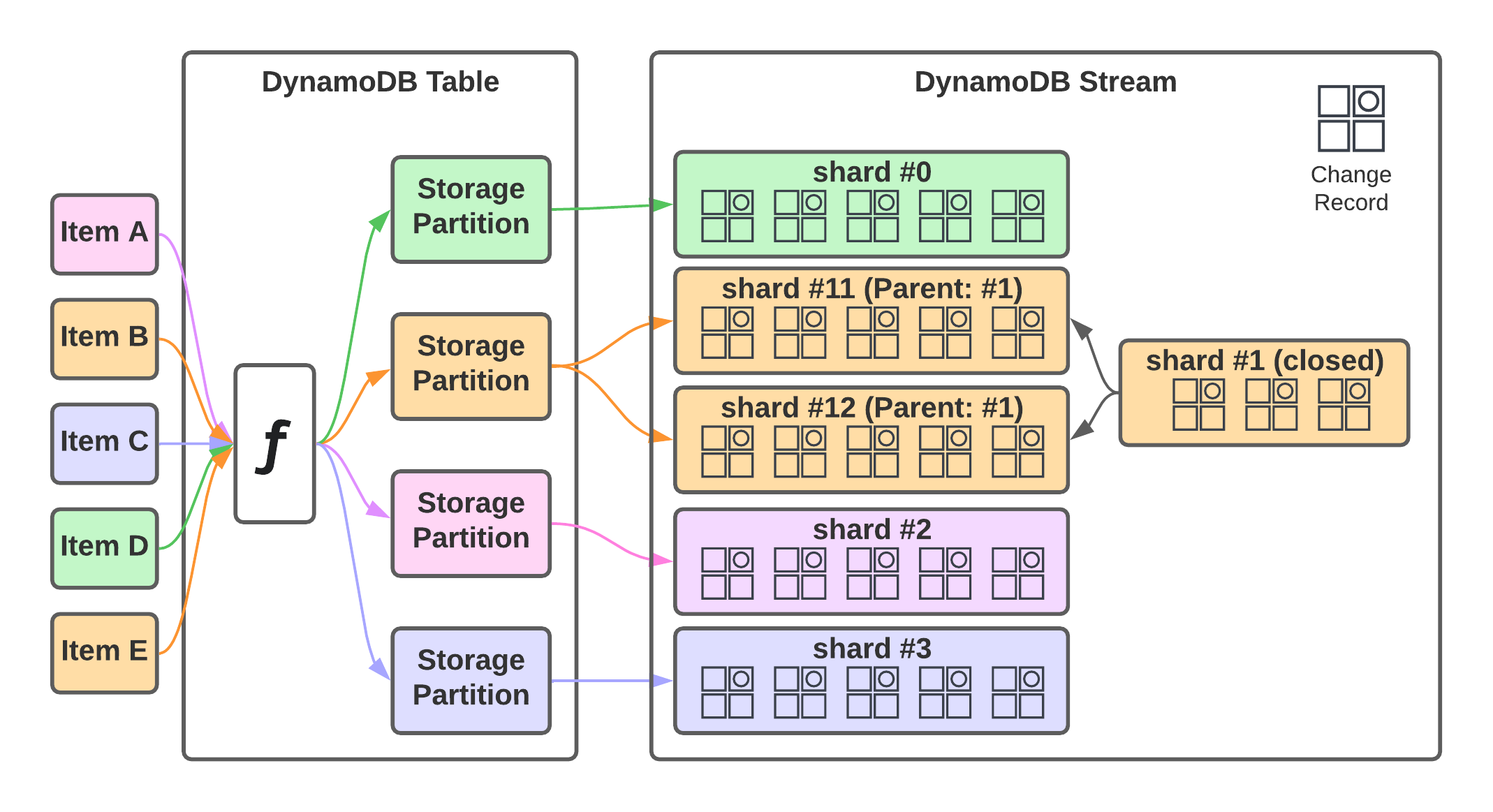

DynamoDB streams are a way to do change data capturing in tables. That means changes to items are written into a stream, not unlike a transaction log from a traditional relational database. Applications can consume this stream of changes to respond to changes in the data. The application starts to read somewhere in the stream and then consumes every successive changed record. This is pretty simple as long as the table only consists of a single storage partition. In practice, that’s rarely the case, though.

DynamoDB scales to the level of storage or throughput requirements by increasing the number of partitions until sufficient capacity is available. That adds complexity. It’s not unusual to have tables with hundreds or even thousands of these storage partitions. This means the stream component has to be able to scale out too. It does that by the use of sharding. A shard in a stream is similar to a table’s storage partition. Each storage partition has at least one shard. Shards store the stream of changes in the particular storage partition for 24 hours.

Whenever we talk about reading from a DynamoDB stream, we’re talking about reading from the shards that make up the stream. The number of these shards is not static. It can increase or decrease over time depending on what happens in the table. New storage partitions increase the number of shards. Many reads and writes to a storage partition can cause a shard to fill up and split it in two. Shards can also naturally fill up and then get a successor.

The lineage of shards is tracked to make this transparent. Each shard may have a parent shard. When processing records from a stream, you must process the parent before the children to preserve the order of events. The DescribeStream API can be used to get the list of current shards. Here is an example of that:

$ aws dynamodbstreams describe-stream --stream-arn <stream-arn>

{

"StreamDescription": {

"StreamArn": "arn:aws:dynamodb:eu-central-1:123123123123:table/pk-only/stream/2022-03-19T13:37:17.440",

"StreamLabel": "2022-03-19T13:37:17.440",

"StreamStatus": "ENABLED",

"StreamViewType": "NEW_AND_OLD_IMAGES",

"CreationRequestDateTime": "2022-03-19T14:37:17.433000+01:00",

"TableName": "pk-only",

"KeySchema": [

{

"AttributeName": "PK",

"KeyType": "HASH"

}

],

"Shards": [

{

"ShardId": "shardId-00000001647710671110-c100053c",

"SequenceNumberRange": {

"StartingSequenceNumber": "1624739500000000027768819660",

"EndingSequenceNumber": "1624739500000000027768819660"

},

"ParentShardId": "shardId-00000001647697037779-1c062810"

},

{

"ShardId": "shardId-00000001647796385437-c1637cb4",

"SequenceNumberRange": {

"StartingSequenceNumber": "1629451500000000049791965989"

},

"ParentShardId": "shardId-00000001647780605726-c21455bb"

}

]

}

}

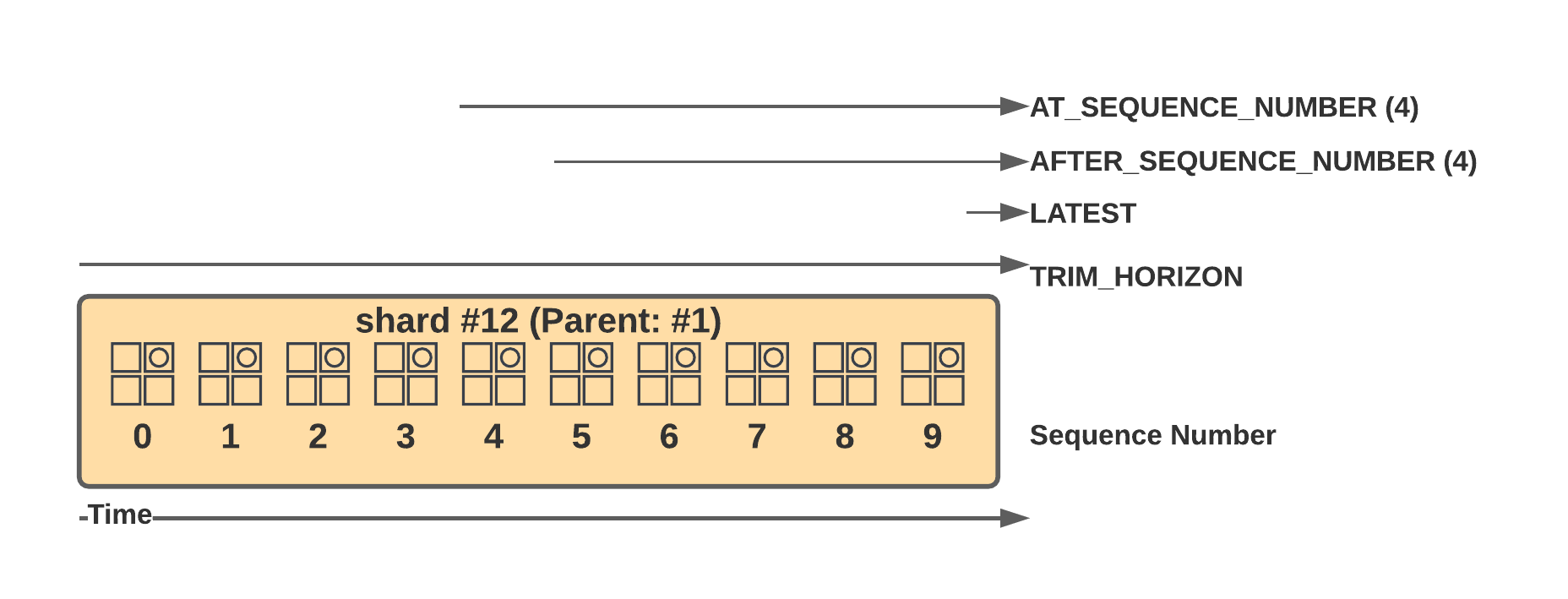

We need a shard iterator to request the records from a shard and receive one by the GetShardIterator API. This shard iterator acts as a pointer in the stream of changes. You can define where this pointer should point to initially by the shard iterator type. Setting it to TRIM_HORIZON causes it to start at the oldest record available in the shard. Choosing LATEST returns the most recent one, and AT_SEQUENCE_NUMBER or AFTER_SEQUENCE_NUMBER allows you to specify exactly where to start reading from in combination with the SequenceNumber parameter. Note that these iterators expire after about 15 minutes, so you need to request the records within that time frame.

$ aws dynamodbstreams get-shard-iterator --stream-arn <stream-arn> --shard-id <shard-id> --shard-iterator-type TRIM_HORIZON --no-cli-pager

{

"ShardIterator": "arn:aws:dynamodb:eu-central-1:123123123123:table/pk-only/stream/2022-03-19T13:37:17.440|2|AAAAAAAAAAIuaQ...HjeCPZPrVe6Bk1Hsa6PrTQ=="

}

Now that we have a shard iterator, we can finally request the records from our shard. The aptly named GetRecords API exists to do precisely that. We pass it our shard iterator, and it returns the items in the shards and a new shard iterator. There weren’t any records in the shard in my example, but now would be the time to process the change records.

$ aws dynamodbstreams get-records --shard-iterator "arn:aws:dy..."

{

"Records": [],

"NextShardIterator": "arn:aws:dynamodb:eu-central-1:123123123123:table/pk-only/stream/2022-03-19T13:37:17.440|2|AAAAAAAAAAIjO5vOr8skH8j49FiK34qRqbSjjwjSa07EgMz1qxOsmDE3W5CrFVKz1UkQXdfkYIxTH2tjfvUkyP0hNQgDqsLoP...bUboSb1y1k6S2Y"

}

To summarize, there are quite a few things we need to manage when we want to process data from DynamoDB streams in our custom application. We need to adapt to changes in the number of shards and shard lineage. We also need to ensure that we read all changes within 24 hours. Otherwise, we’ll lose data. That’s a lot of work. What kind of guarantees do we get for that? The documentation mentions that change data will become available in the shards in near real-time so that we can respond very quickly. Also, the stream guarantees that changes to a specific item will be written to the stream in order - but: we need to make sure first to read the parent before the child shards. Last but not least, each record will appear exactly once within the stream. This last part is nice, but we’ll soon see that it’s more complicated with Lambda.

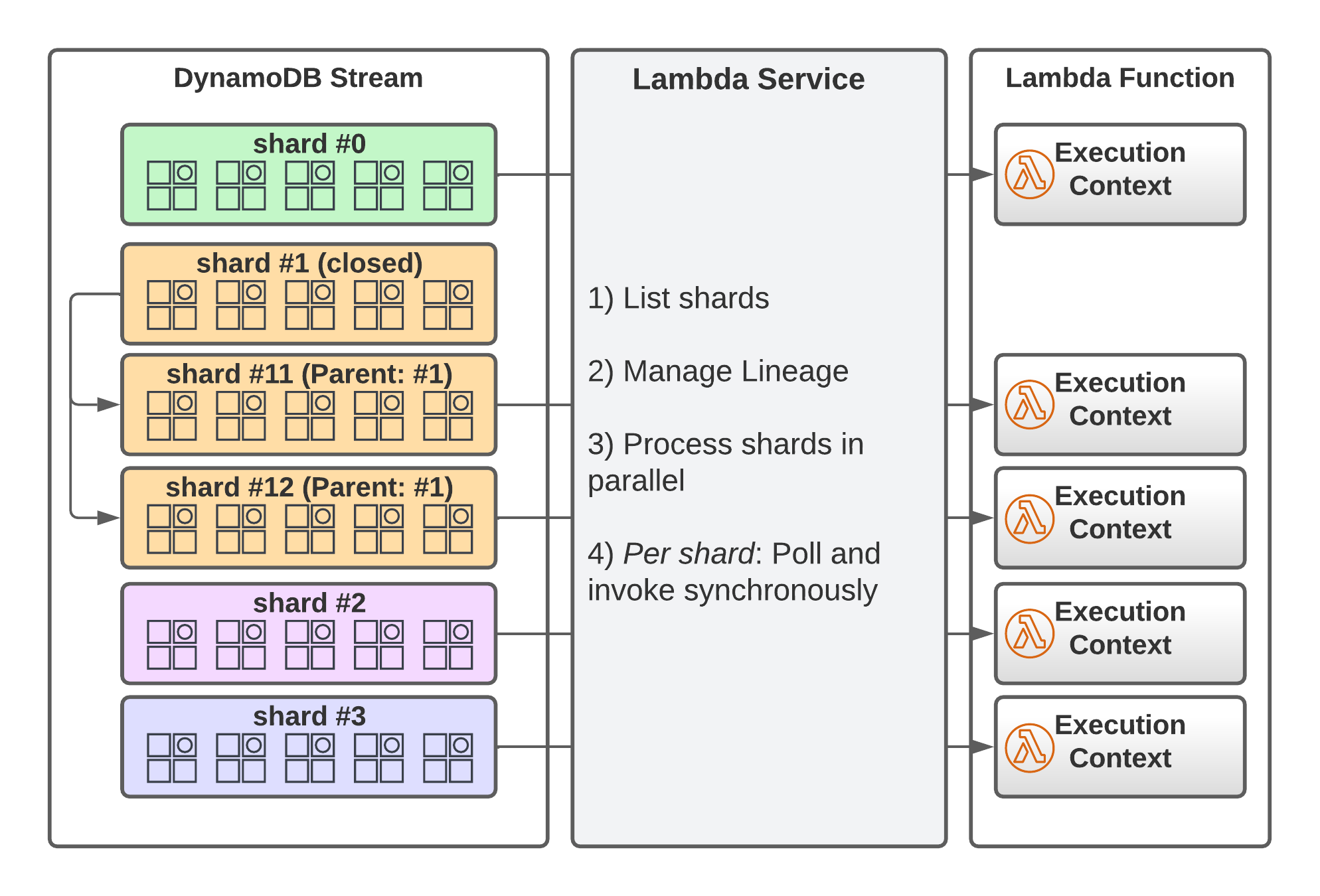

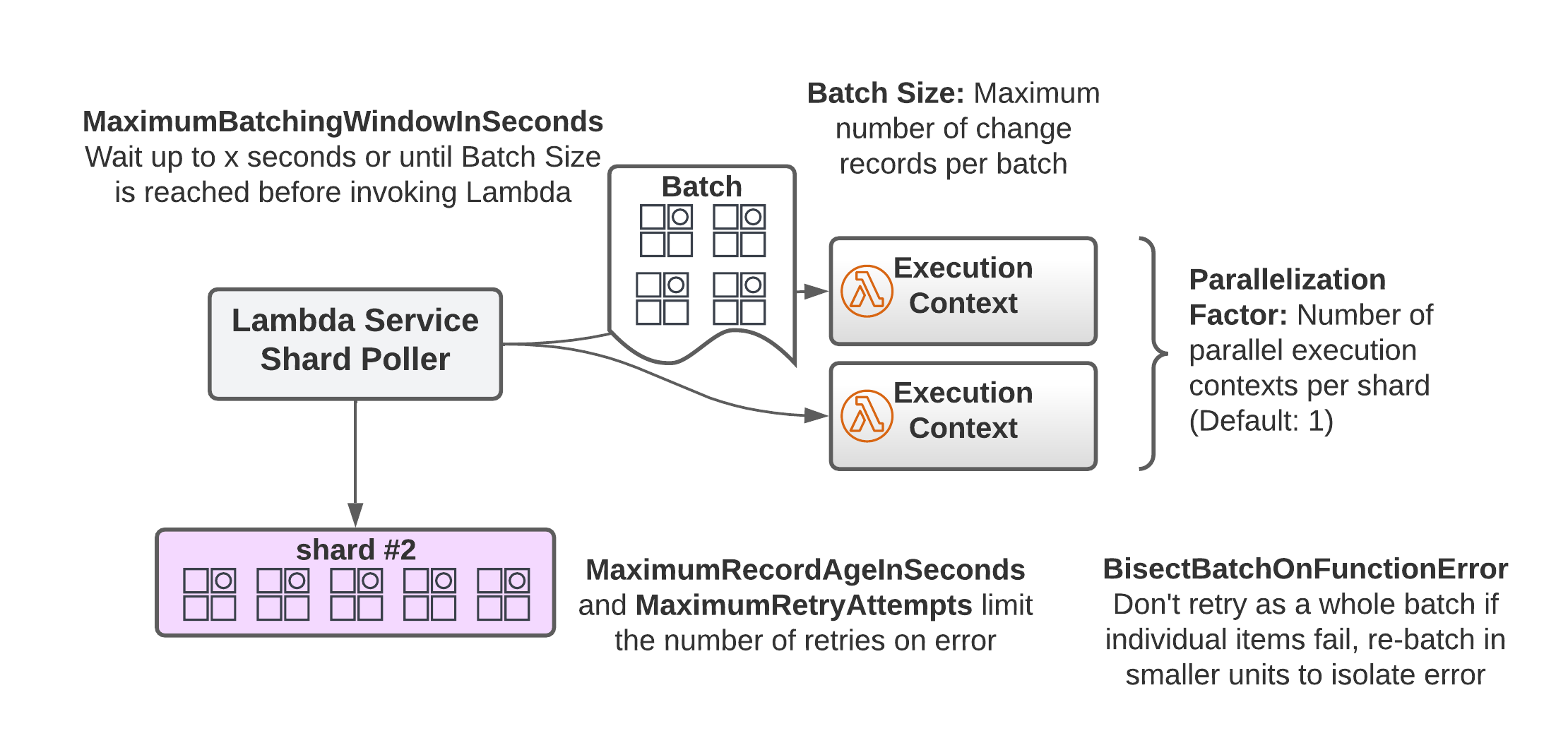

Before we talk about the complications, let’s see how the integration between Lambda and DynamoDB streams works. To use the integration, you need to give the permissions for the API actions mentioned above to the execution role of your Lambda function. The Lambda service (not your code, the service) will automatically list the stream’s shards. A process for each shard polls the shard for records four times per second using a shard iterator. This process takes care of lineage so that parent shards will be processed first. If it finds records, it will invoke your lambda function synchronously, and, depending on the response, either poll again or retry the batch of records if something goes wrong.

We have a little more control over this process than I mentioned. We can configure where the stream processing should start in the log by specifying TRIM_HORIZON or LATEST, and now you know what that’s for. Additionally, we can control batching. We can tell Lambda to invoke our function with at most n records by configuring the BatchSize. The MaximumBatchingWindowInSeconds tells Lambda for how long to gather events up to BatchSize until it invokes your code. This is a way to avoid invoking your code with tiny batches.

One more thing is the ParallelizationFactor which allows you to increase the number of execution contexts per shard up to 10. That can be useful if you have very high throughput on your table. Lambda will still ensure that the order of records is preserved at the item level. In contrast to the native streams, you get the guarantee of at least once delivery opposed to exactly-once delivery. That’s the case because Lambda will retry batches if there is an error during execution. By default, it retries the whole batch, but it can also divide it into two smaller batches if BisectBatchOnFunctionError is set to true. This helps isolate the records that cause the error. Using the MaximumRetryAttempts and MaximumRecordAgeInSeconds allows you to control how many retries are performed for erroneous batches.

Which Batch Size and Parallelization Factor should you pick? It depends, as usual. The batch size controls up to how many records you can get per Lambda invocation. Set it to one if your code is written to only handle one change record at a time. Otherwise, you can increase it up to ten if you can process the change records within the Lambda timeout. Concerning the parallelization factor, you can set it as high as possible if there is no adverse impact on whichever backend system you’re talking to. Lambda still ensures that the order of changes per item is preserved. A high parallelization factor can decrease the average time for responses to changes.

Tweaking these parameters allows you to optimize change data processing in your serverless application. This is where we call it a day. We’ve covered how DynamoDB streams work under the hood and how the Lambda service integrates with them to facilitate responding to changes in your data. Thank you for reading this far. Hopefully, you enjoyed reading this post as much as I enjoyed writing it. If you’re interested in more details about using DynamoDB, check out my introduction to DynamoDB in 15 Minutes or my post outlining the process of NoSQL database design through the example of modeling a product catalog in DynamoDB. For some more niche topics, there’s a guide about working with lists in DynamoDB and a post about implementing optimistic locking in DynamoDB with Python.

Hopefully, you enjoyed reading my work. I’m looking forward to questions, feedback, and concerns.

References