Introduction to asynchronous interactions with the AWS API in Python

The world is asynchronous, as Dr. Werner Vogels, the Amazon CTO, recently proclaimed at re:invent 2022. He means that asynchronous systems and operations are ubiquitous in nature and computer science, even though most of us write synchronous code, especially when working in a language such as Python. Today, I want to explore the current state of asynchronous computing in Python concerning interacting with AWS services. I will explain the basic building blocks and how to use them to interact with AWS services through an example.

One of the goals of writing asynchronous code is to improve resource utilization. Especially I/O operations like interacting with storage devices or services over the network are incredibly slow from the processor’s perspective. While waiting for a web service’s response, the processor can perform a lot of meaningful work. It also does that at the operating system level, but within our own python code, that’s typically not the case.

By default, most I/O operations in Python are blocking operations, meaning they block the flow of program execution until they’re completed. Especially when our code makes a lot of calls to 3rd party APIs like AWS, we leave a lot of valuable computing time on the table if we don’t do stuff while waiting for the response. But how can we do that? An answer lies in the asyncio module of the standard library. There are other approaches such as (multi-) threading and multiprocessing which we won’t go into here. If you’re unfamiliar with asyncio, I highly recommend you check out this article by realpython.com. It’s an excellent overview of the topic.

I will give a highly simplified explanation of the basic building blocks in Python. For more details, read the article mentioned above. Writing asynchronous code in Python has been possible since Python 3.4, although the feature matured until Python 3.7. The two most important keywords are async and await. We use async before a function to define it as asynchronous. Under the hood, this means it can be paused while waiting for things to happen. It also allows us to use the await keyword in the function body, which is not permitted outside of async functions.

Basically, you can call a function that has been defined as asynchronous and will receive a so-called awaitable as the immediate response. The function won’t be executed immediately, but when there’s compute time available. After you call an asynchronous function, you can continue your regular program flow. If you need the result of the function call, you await the awaitable, which will block your code until the other function is done executing.

Here’s an example function that doesn’t do much except wait for a random time. Instead of waiting, you’d usually call a third-party API or read files from storage.

import asyncio

import random

import time

import typing

async def sleepy_boi(name: str) -> int:

"""Sleeps for a bit and returns the number of seconds it slept for."""

# In practice, this would be I/O operations

sleep_for_s = random.randint(1, 5)

await asyncio.sleep(sleep_for_s)

print(f"Sleepy Boi {name} woke up after {sleep_for_s}s")

return sleep_for_s

We need another piece of the puzzle to see how this can benefit us. The asyncio.gather function allows you to pass in multiple awaitables, and it can wait for all of them to finish computing. Here’s an extension of the example above that receives the number of asynchronous operations to start and then calls sleepy_boi as many times as necessary:

async def sleepy_bois(number_of_bois: int) -> typing.List[int]:

"""Calls many sleepy bois"""

return await asyncio.gather(

*[sleepy_boi(f"boi_{i}") for i in range(number_of_bois)]

)

If you paid close attention, you have noticed that we can only use await within a function defined as async, so how do we wait for the first asynchronous function? The first asynchronous function is called using asyncio.run(sleepy_bois(argument)), which will implicitly await that function.

def main():

"""Main function that triggers the async magic."""

start = time.perf_counter()

result = asyncio.run(sleepy_bois(5))

runtime = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"It took {runtime:.3f}s to execute, the total wait time was {sum(result)}s.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

This has been a bunch of code; let’s execute it to see what happens.

$ python async_example.py

Sleepy Boi boi_4 woke up after 1s

Sleepy Boi boi_0 woke up after 4s

Sleepy Boi boi_2 woke up after 4s

Sleepy Boi boi_3 woke up after 4s

Sleepy Boi boi_1 woke up after 5s

It took 5.005s to execute, the total wait time was 18s.

As you can see, the five calls finished in about 5 seconds, even though the total wait time was 18 seconds. This is the power of asynchronous execution.

Sounds great. How can I use this with boto3? Well… you can’t directly. There’s no native support in boto3 for this, but fortunately, a third-party package wraps around boto3 to make this possible. It’s called aioboto3 and has been around for a while. It supports almost everything the boto3 does, but the syntax is slightly different because of all the asyncs and awaits.

You can install the module using pip: pip install aioboto3 and then check out the docs for some usage information. To be honest, the documentation could use some more work, but it isn’t that tricky. Let me show you how to use it with a real-world example.

Scenario

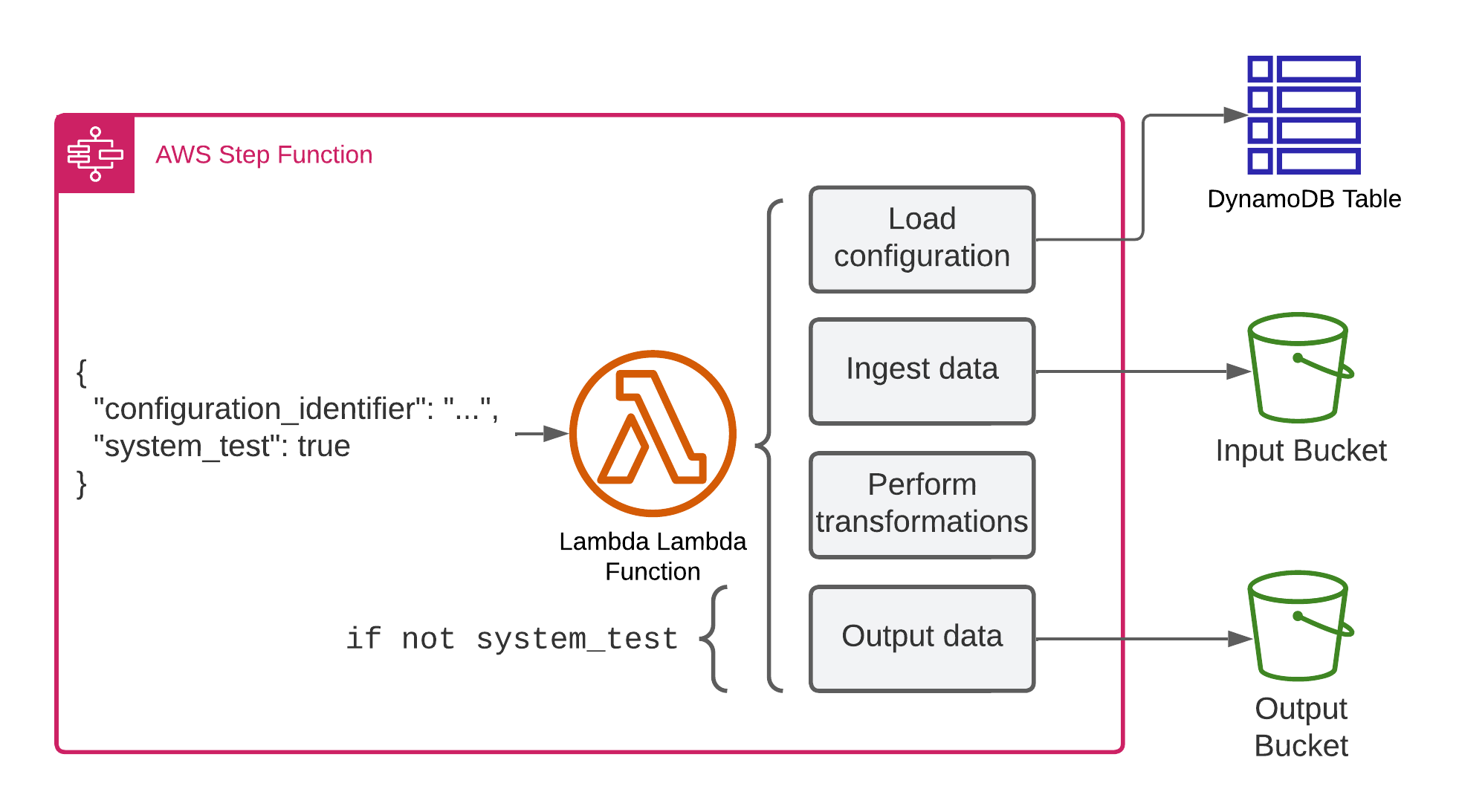

In a recent project, we had a Lambda function that performed some computation based on a configuration (about as generic as it gets). It’s triggered from a step function with a configuration identifier, downloads the configuration, then fetches some data from S3, performs a transformation, and stores it in S3.

Unfortunately, we encountered problems during deployments because some configurations didn’t match the capabilities of the current iteration of the Lambda function. Since this kind of in-depth configuration validation is non-trivial, we opted for the following approach. We added an optional system_test flag to the Lambda event, and if that’s true, the function will perform all operations except storing the output data, thereby not changing any state 1.

To perform this system test, we need to trigger the Lambda function synchronously (Invocation type RequestResponse) with each configuration identifier and check the output. Later, this will be done through a step function with a map state and some parallelism. A short-term fix for this problem involves a script that will become part of the deployment pipeline.

In pseudocode, this script is extremely trivial:

all_configurations = list_configurations()

for configuration in all_configurations:

response = invoke_lambda(configuration.identifier)

report_result(response)

The problem is that this is very inefficient as there is no parallelization. Since this is mainly I/O limited, i.e., we’re waiting for the Lambda function to respond, an asynchronous approach can benefit us. Before we look at that, let me show you a dummy Lambda function you can use to follow along:

import random

import time

def lambda_handler(event, context):

print(event)

sleep_time = random.randint(1, 10)

print(f"Sleeping for {sleep_time}s")

time.sleep(sleep_time)

if random.randint(1, 100) <= 15:

# 15% chance of errors

raise ValueError("Something went wrong!")

return {

"configuration_identifier": event.get("configuration_identifier"),

"slept_for": sleep_time,

"system_test_successful": True

}

This lambda function sleeps for a random number of seconds between one and ten. It fails in about 15% of all invocations, simulating a broken configuration. In all other cases, it returns the message that processing was successful. Let’s look at the implementation now. You can find the complete code on Github if you’re interested.

The main function sets up logging and generates a few dummy configuration identifiers, which it then uses to start the system test using asyncio.run() to invoke the async function. After the test is done, it logs some information about the results.

def main() -> None:

"""Generates configurations for the system test, triggers it, and reports the result."""

LOGGER.addHandler(logging.StreamHandler(sys.stdout))

LOGGER.setLevel(logging.INFO)

configuration_identifiers = [f"config_{n}" for n in range(40)]

start_time = time.perf_counter()

results = asyncio.run(run_system_test_for_configurations(configuration_identifiers))

runtime_in_s = time.perf_counter() - start_time

LOGGER.info("The system test took %.3fs", runtime_in_s)

counts = collections.Counter(results)

LOGGER.info(

"%s of %s passed the test - %s failed",

counts[True],

len(configuration_identifiers),

counts[False],

)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

The run_system_test_for_configurations asynchronous function calls run_system_test for each configuration it has received in the parameter and uses asyncio.gather to await all results and return them in a single list.

async def run_system_test_for_configurations(

configuration_identifiers: typing.List[str],

) -> typing.List[bool]:

"""Schedules system tests for all configurations and waits until they're done."""

return await asyncio.gather(

*[

run_system_test(config_identifier)

for config_identifier in configuration_identifiers

]

)

run_system_test is where the magic happens. It instantiates an aioboto3.Session, which you use to get an asynchronous client or resource object that you may be used to from boto3. It then uses this session to create a Lambda client and invoke the Lambda function. Note the await before the invocation. This causes it to pause until the API call returns a response. Once the response is available, we check if an error occurred, report it accordingly and return False. Otherwise, we retrieve the payload, which is any asynchronous operation again, and log it for debugging before returning the result of the function.

async def run_system_test(configuration_identifier: str) -> bool:

"""Invoke the lambda function with the configuration identifier and parse the result"""

session = aioboto3.Session()

async with session.client("lambda") as lambda_client:

response = await lambda_client.invoke(

FunctionName=LAMBDA_NAME,

InvocationType="RequestResponse",

Payload=json.dumps(

{

"configuration_identifier": configuration_identifier,

"system_test": True,

}

),

LogType="Tail",

)

if "FunctionError" in response:

await format_error(configuration_identifier, response)

return False

LOGGER.info("Configuration %s PASSED the system test", configuration_identifier)

payload: dict = json.loads(await response["Payload"].read())

LOGGER.debug("Payload %s", json.dumps(payload))

return payload.get("system_test_successful", False)

There are a few oddities to wrap your head around here. First, we need a session to create a client. You can do it similarly in boto3, but the implicit session is usually used. For aioboto3, the session is mandatory. The other unexpected behavior is await response["Payload"].read(). I got tripped up by this at first, but it makes sense if you consider that the whole point of asyncio is to make I/O operations asynchronous. The API call returns a StreamingBody data type, and reading it is a form of I/O.

If we run the script, we’ll find a similar result to the pure python example above. We were able to test 40 configurations in about 14 seconds, and this process should scale quite well.

$ python aio_boto3.py

[...]

Configuration config_28 PASSED the system test

Configuration config_36 FAILED the system test

The error message is: Unhandled

============================== Log output ==============================

START RequestId: 4356aa76-9d26-4601-ace2-f6ded8cf8d0c Version: $LATEST

{'configuration_identifier': 'config_36', 'system_test': True}

Sleeping for 8s

raise ValueError("Something went wrong!")2, in lambda_handler

END RequestId: 4356aa76-9d26-4601-ace2-f6ded8cf8d0c

REPORT RequestId: 4356aa76-9d26-4601-ace2-f6ded8cf8d0c Duration: 8012.19 ms Billed Duration: 8013 ms Memory Size: 4096 MB Max Memory Used: 70 MB Init Duration: 471.54 ms

============================== End of log ==============================

Configuration config_35 PASSED the system test

Configuration config_12 PASSED the system test

Configuration config_7 PASSED the system test

Configuration config_31 PASSED the system test

Configuration config_10 PASSED the system test

The system test took 13.927s

35 of 40 passed the test - 5 failed

That’s it for today. I have explained the motivation behind asynchronous computing and how it can be used within Python. I’ve also shown you a real-world example of how it can be used.

Hopefully, you gained something from this blog, and I look forward to your questions, feedback, and concerns.

— Maurice

P.S.: Check out the code on Github

Title Photo by Lan Pham on Unsplash

-

Yes, this is not a very efficient implementation. It uses quite a bit of computing capacity. Nevertheless, it’s a very valuable post-deployment check because it’s an in-depth check with actual data. It’s pragmatic. ↩︎